The concept of human races has been around since 1735 when Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus proposed a classification system placing humans into four distinct “races” based on perceptions of skin color and geography.

However, over the last eight decades, many biologists and physical anthropologists have increasingly argued that race is, and has always been, an artificial social construct rather than a scientific fact. They maintain that the continued use of the race concept hinders scientific truths about human diversity and that race should not be used as a variable in science-based endeavors, especially in medical research.

Should science writers and science communicators - important links between scientific minds and nonscientific minds - get actively involved in the campaign against using the race concept to explain human diversity?

Looking at the science may be helpful.

We all know that genes hold the “blueprints” for life. Alleles, located on specific genes, produce a variety of observable characteristics, called “phenotypes.” We and our genes live in “gene pools,” a term used to account for all of the phenotypic variations in a given population. Genes “flow” in and out of gene pools as people wander the Earth and, sometimes, produce offspring with people who are phenotypically greatly different than themselves.

When genes and the traits they carry “flow” in and out of a gene pool the result can be a mosaic of physical features, combinations of features which may or may not conform to stereotypic characteristics typically thought of as representative of one “race” or another.

It useful to remember that the distribution of phenotypes in the premodern world was more geographically restricted than today because oceans, mountains and great distances did not allow people to easily “mix” their genes. Phenotypes tended toward local similarity.

In 1989, when I was a graduate student in anthropology and also the media relations person for the American Anthropological Association, anthropologist Leonard Lieberman and colleagues published “Race and anthropology: A core concept without consensus.” The authors maintained that the race concept was losing credibility as it was based on "imaginary clusters of traits."

They also pointed out that there is often as much - or more - phenotypic variation within perceived races than between them. To speak accurately about human phenotypic diversity, the authors advocated the model offered by Frank Livingstone in 1962 when he said (now famously) "there are no races, only clines."

A cline, first described by evolutionary biologist Julian Huxley in 1938, is a construct for explaining how phenotypes, such as skin color, eye lid shape, hair texture and blood types, even genetic susceptibility to diseases, vary in prevalence within populations and over a geographical gradient. A cline can show how traits – when considered one-by-one rather than together– may be strongly represented here, but gradually appear less often, or eventually not at all, there.

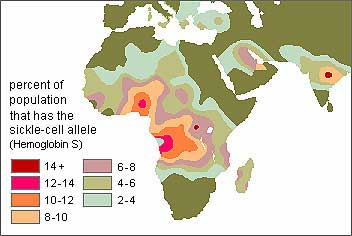

A cline can also be used to demonstrate the prevalence and geographical patterns of genetically based diseases, such as the sickle-shaped red blood cell trait that can cause sickle cell anemia, and Tay-Sachs disease, a rare nervous system disorder. A cline can show high prevalence of the sickle cell trait in West Africa and some areas of the Middle East, but also shows how little the trait appears, if at all, in East or South Africa.

Lieberman and colleagues added that cline could not be used to replace race – it is a greatly different, yet accurate concept.

In 1970, Thomas Kuhn suggested in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions that a paradigm, a mental model, is prerequisite to perception. Kuhn said that once a paradigm is constructed, anomalies, or "minor breakdowns" within the paradigm, create tension in the model. "As time goes by and new demands are made on the lexicon, conditions may be encountered that defy description," Kuhn said.

Kuhn concluded that a conceptual paradigm shift can be expected when anomalies become “incommensurate” with the concept. Such is the case for race.

All classifications are dependent upon descriptive language, yet the lexicon often becomes inadequate to the descriptive task as contrary new concepts and theories are validated. New words must come into use to support descriptive accuracy. If “race” defies valid scientific description, that reality also makes demands on the language we use to describe human variation.

If race is not a legitimate concept and, therefore not a useful variable for science, should it be a legitimate concept for science writers and science communicators?

The argument for science writers and science communicators to get involved in the no- such-thing-as-race effort is that, like scientists, we are obligated to present valid scientific explanations of the world and of ourselves. That responsibility should probably include presenting accurate scientific models for explaining human diversity.

The argument against science writers and communicators enlisting in the “no-such-thing-as -race” effort is that we are not charged with the responsibility of correcting scientists - should they use the term. We are charged only with accurately reporting on the information scientists generate.

By: Randolph Fillmore

Randolph Fillmore is a science and medical writer and an adjunct professor of anthropology and mass communications at Hillsborough Community College in Tampa, Florida, USA. He is the director of Florida Science Communications (www.sciencewriter.ink), a member of the National Association of Science Writers in the U.S. since 1994, and has recently joined the Science Writers and Communicators of Canada.