How can science writers and communicators cover vaccine science effectively in a climate where more than more than half of Canadians worry about potential side effects of all vaccines and nearly half would hesitate or reject a COVID-19 version even in the midst of a pandemic?

A roundtable at SWCC 2020 uncovered some insights. It featured science communication researcher Alice Fleerackers, social psychology professor Dr. David Hauser, immunology researcher Dr. Angela Crawley, and visual science communicator Mona Li.

“Vaccine hesitancy” is a global problem, one named in 2019 as one of the top 10 global threats to human health by the World Health Organization. Extensive evidence indicates vaccines are both safe and effective, yet divisions persist internationally among both the public and scientific community. This contributes to decreased vaccination rates and hundreds of thousands of vaccine-preventable deaths every year.

Jumping to conclusions

Calls to combat vaccine hesitation often focus on “fake news” and misinformation. But preliminary research by Hauser and master’s student Andrew Hall at Queen’s University suggests these beliefs may have a deeper root: jumping to conclusions cognitive style (JTC). This is the tendency to make judgments with very little information.

JTC is usually studied within the context of conditions, such as schizophrenia or panic disorder. But Hauser and Hall’s study—which is yet to be published—examined its connection to vaccine-related beliefs.

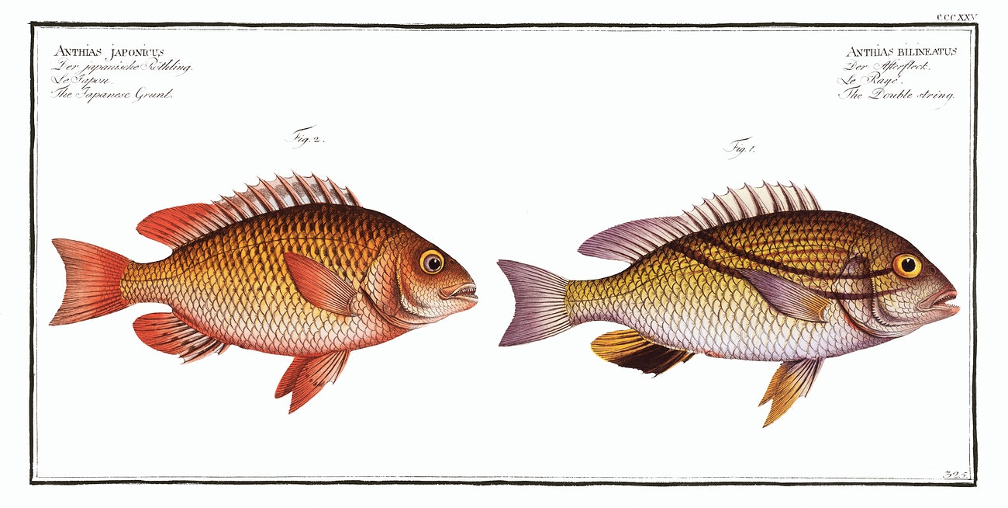

The duo presented study participants with a fictional scenario about two lakes, each populated with two different kinds of fish, but in each lake, one kind of fish was more common. . Each person received one piece of “evidence” (i.e. a fish that was caught in one of the lakes) and was asked to figure out from which lake it had come. They could either ask to see more evidence (i.e. more fish), or make a decision right away.

Most people asked for more evidence, but as many as 40 per cent did not; they needed only one piece of information to “jump” to a conclusion. It turns out those same people were also more likely to be concerned about vaccines having adverse effects or to believe in conspiracy theories about them.

For Hauser, one of the most interesting takeaways is the disconnect between what vaccine skeptics say and what they do.

“People who are skeptical of vaccines often say that… ‘we need to get more information before we can declare them to be safe,’” he says. “But it doesn’t seem like they have a ‘search for all the evidence’ cognitive style—the evidence we have seems to suggest the opposite.”

Herein lies a challenge for science communicators, especially in our “post-truth” reality: how to encourage audiences to engage more critically with vaccine (mis)information rather than jumping to conclusions?

Learning from past media coverage of vaccine science

In her work as an immunology researcher at the University of Ottawa, Crawley has been closely watching media coverage of the COVID-19 vaccine. In a breakout session at SWCC 2020, she worked with participants to brainstorm strategies to cover COVID-19 vaccine research. They discussed lessons from the past, such as media coverage of the infamous Andrew Wakefield study that (fraudulently) linked the MMR vaccine to autism.

One pain point raised during the discussion was just how hard it is to ensure scientific research is accurate —both for scientists evaluating it and communicators covering it. It’s a challenge amplified for COVID-19, where so much research is only available in preprint—publicly accessible but not yet peer reviewed.

To ensure this preliminary research is accurate and valid, SWCC 2020 participants stressed the importance of collaborating with scientists and being upfront about limitations.

“Work together with experts in the field to interpret [preprint] scientific articles to be conveyed to the public,” suggested one participant. “State that the study has not been vigorously peer reviewed,” offered another.

Being explicit about scientific uncertainty isn’t always easy, but researchers believe it can build audiences’ trust in science, help them make better decisions, and engage them more deeply with the scientific process.

Communicators may also have to play an educational role here.

“Add a layer of understanding before sharing new or current research,” one participant offered. “Provide a common language and information that is very foundational.”

Crawley agrees, encouraging communicators to include key immunology basics in any COVID-19 vaccine coverage.

“Explain how the herd immunity percentage is calculated, and use this as a means to try to encourage as much vaccine uptake as possible,” she says. “Give the public some insight into those processes.”

Communicating with compassion

Building trust is about more than facts. A wealth of research highlights the importance of emotion in decision making, including in parents’ decisions about whether or not to vaccinate their children.

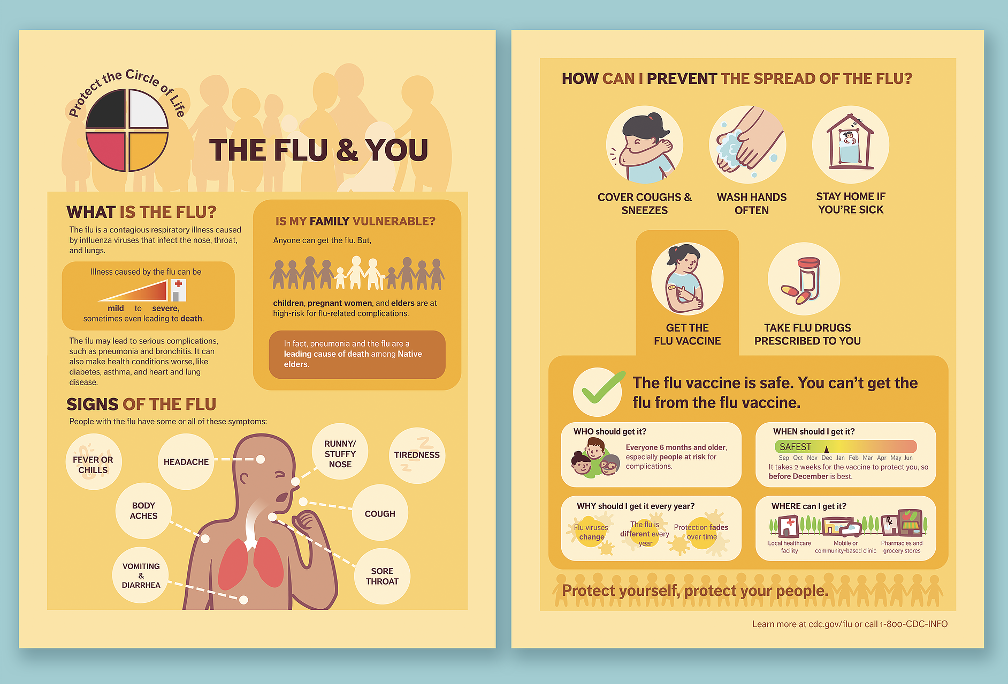

Li, who specializes in biomedical visuals, advocates for an empathetic, user-centred approach. At SWCC 2020, she explained how using visual formats, like comics and visual narratives, can bring a “human side” to science communication. She also offered advice for getting to know the perspective of the end-user in vaccine communication, such as building personas to get to know your audience. Ask: What do they already know about this topic? What do they value? What are their doubts and fears? Answering these questions is a first step towards effective empathetic communication.

In Li’s breakout session, participants brainstormed how to apply these strategies in their own work. Key takeaways included the importance of building authentic relationships with people who feel hesitant about vaccination and of sharing personal experiences, rather than facts and statistics.

“Large institutions are [often] very disconnected from individuals who they are trying to get to ‘listen,’” one participant said. “Dismissive messaging from experts may further divides.”

“We may think we are talking to hypothetical ‘others,’” added another participant, highlighting the importance of understanding the thoughts and feelings of these “others” before attempting to convince them of your own point of view. “People around us probably have all kinds of different beliefs!”

Taking the time to understand those beliefs, participants agreed, should be part of any vaccine communication strategy.

“We may worry about exposing too many things that the public can critique,” one participant said. But the consensus was that vulnerability could open doors for more effective messaging.

“Meet the audience where they are, acknowledge their concerns, feelings, and experiences—as well as your own...Communication should be more of a two-way conversation.”

To watch the full session, visit the SWCC Conference Session Recordings.

By: Alice Fleerackers, with insights from Dr. David Hauser, Dr. Angela Crawley, Mona Li, and participants of the SWCC 2020 Annual Conference.