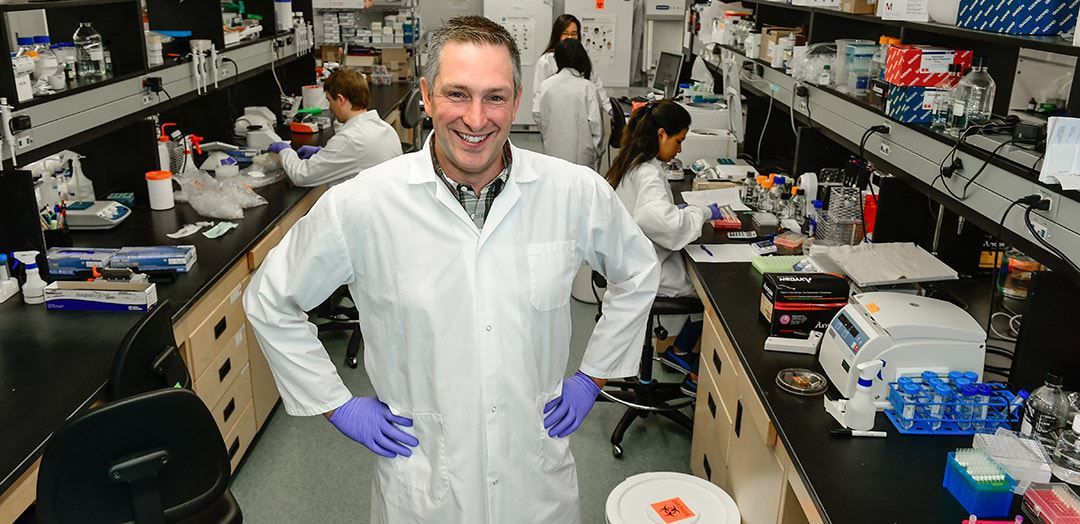

Darryl Falzarano at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization - International Vaccine Centre (VIDO InterVac) at the University of Saskatchewan. Photo: Debra Marshall

If the current pandemic has taught us anything, it is to bring into stark relief just whose work is essential.

Around the world, people are coming out to yards and balconies to applaud health care workers. People have new appreciation for oft-ignored sanitation workers and grocery store clerks.

While we cheer on those who keep the wheels of society turning, let’s also spare a thought and some words of thanks for another overlooked, essential group: scientists.

Some years ago, while working at the University of Saskatchewan, I wrote a brief profile on a new faculty member, a young researcher named Darryl Falzarano. His chosen subject was an obscure (to me) disease called Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, or MERS.

Why, I wondered, was he mucking about with something that, while serious, wasn’t terribly contagious and affected populations on the other side of the world? Plus, the animal reservoir for the MERS virus was the camel – a species not often seen on the Canadian Prairies.

He explained that MERS was a coronavirus, a close relative of SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome). SARS I knew: the epidemic had been in the news around the world. People had died; people were afraid.

MERS and SARS are zoonotic diseases, that is, they originated in animals. These diseases constitute the majority of emerging threats to human health. Know more about MERS, Falzarano said, and we know more about zoonotic coronaviruses.

I eventually left the university and lost track of Falzarano until early this March. There was an announcement that VIDO InterVac at the University of Saskatchewan was getting a sudden multi-million-dollar funding infusion from the Canadian government. A new coronavirus had gone pandemic: SARS CoV-2, which causes COVID-19. Once again, people are dying. People are afraid.

VIDO InterVac, one of the top vaccine development organizations in the country, is tasked with developing a vaccine against the threat. Falzarano leads the team.

As any emergency preparedness professional knows, when a crisis hits, there is no time to plan. The plan must be in place, the people trained, the facilities ready.

Most scientists labour in obscurity, making incremental discoveries and publishing them in journals that are largely read only by their peers. But when a crisis comes, when their expertise is needed, they are ready.

What drives scientists to do what they do? Joy of discovery? Insatiable curiousity? Desire to help society? I suspect the reasons are as varied as the people. Of one thing I am certain: scientists don’t get into it for the money. I remember being shocked to learn that a new assistant professor was being paid slightly less than me, a mere research communications officer. This, for someone who had spent at least eight to 10 years completing undergraduate, graduate, and post-doctoral education and training.

Their job was and is much harder than mine. Academic researchers must design and run their research programs, apply for and secure grants, hire and supervise graduate students, write up their research for professional journals, teach classes, and serve on university committees. To get it all done, their work schedule can be brutally long.

And every once in a while, scientists’ expertise becomes critical to the welfare of us all. Suddenly, money is no object. But no amount of funding can conjure a PhD in virology and a decade of hard-won knowledge and expertise out of thin air.

When the call comes, scientists must be ready, and they are. For this, we thank them.

By: Michael Robin

In both the telling and the hearing, stories begin with people.

My passion is taking complex science transforming it into stories that engage and excite. As a strategist, I ask questions. Who are we talking to? Where are they and where do they get their information? What do they believe?

Over more than 30 years, my work appeared in weekly and national publications, broadcast and online media. For more than a decade at the University of Saskatchewan, I worked to identify and shine a light on the innovative minds and discoveries at one of Canada’s top research universities.

We live in challenging times, where innovation and knowledge are often met with rejection and disbelief. This has consequences for issues critical to our species and our environment, from vaccines and genetic engineering to energy and climate change. I believe science writers and communicators have a vital role to play.