|

Reposted from mikethescribe.ca

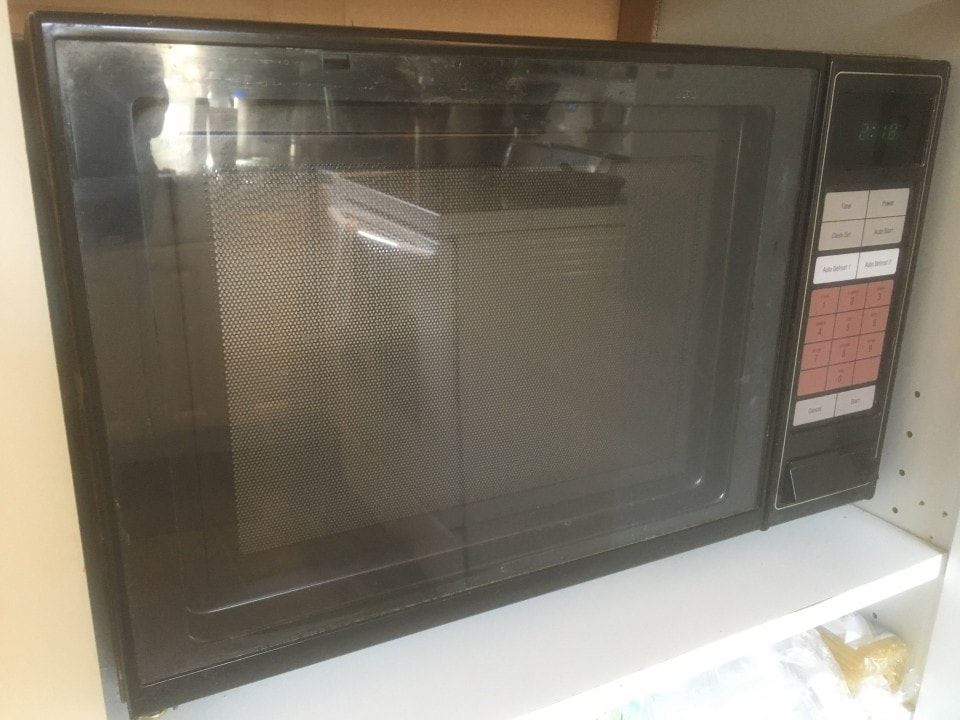

The family radiation cookers. This one is a Beaumark purchased in 1985 and uses microwave radiation. The traditional one in the reflection uses infrared radiation.

Recently, at a meeting in another city, the conversation turned to the example of a new home owner who refused to have a standard appliance installed for fear that it would expose the family to a greater risk of cancer.

Seriously? This one is still out there?

More than 50 years ago, in 1967, Amana Corporation introduced the Radarange, and with it, a whole new way of cooking food. Within a few decades, Amana and other companies had made the microwave oven standard equipment in nearly every kitchen in the developed world.

|

At the same time, there was unease about the new technology, in no small part because of a single word used to describe it: radiation.

My mother remembers newspaper advice columns at the time fielding questions from concerned homemakers about the new devices. They were reassured of their safety, but the unease persists to this day.

What would have happened, I wonder, if instead of “microwave radiation,” they had called it “microwave light?” Both are equally accurate.

Microwave light has wavelengths shorter than radio but longer than infrared. The heat you feel of one of those overhead heaters in a garage is infrared light. Another way to think of wavelengths is colour: the wavelengths of red light are longer than violet, for example.

Microwaves are pretty useful. Some wavelengths resonate with water molecules. That means if you shine microwave light on a water-containing substance, the water molecules start to move faster, or get hot. This is how a microwave oven works.

Microwaves are also used extensively in telecommunications - your cell phone uses them, for instance (typically between 900 Mhz and 1,800 Mhz). Microwaves are used because they can carry much higher information density than radio waves. So, when you’re using your cell phone, you’re using a microwave transceiver RIGHT BESIDE YOUR BRAIN (insert terrified scream here, and yes, I’m being sarcastic).

Popular phrases such as “nuke some dinner” don’t help. People are afraid of radiation, or at least what they think it radiation is. Light does radiate, even if you can’t see it (as I mentioned with the infrared heater). Incidentally, any incandescent bulb actually gives off much more infrared than visible light, which is why you can use them as a heat source.

Also, unless you’ve been very careful or very lucky, we pigment-challenged types have almost certainly had one or more radiation burns in our lives. This is because the shorter the wavelength of the light, the more energy it carries.

Light starts to get dangerous to us once you get into the ultraviolet range, something our sun is quite good at producing. So public health folks urge us to be careful, wear clothing, put on sunscreen to protect from radiation burns that can increase our risk of skin cancer. But we don’t often think of these as radiation burns; we just lament that we were careless and got a sunburn.

Words carry both meaning and emotion. “Light” and “radiation” can often be used interchangeably, but they carry much different emotional baggage. “Natural” and “synthetic” can be used to describe the same product, but how do these words make you feel? How about “organic” or “industrial?” “Corporate” vs “co-op?”

So, when crafting and consuming messages for ourselves and our clients, let us choose our words carefully – not only for meaning but for emotion.

By: Michael Robin

In both the telling and the hearing, stories begin with people.

My passion is taking complex science transforming it into stories that engage and excite. As a strategist, I ask questions. Who are we talking to? Where are they and where do they get their information? What do they believe?

Over more than 30 years, my work appeared in weekly and national publications, broadcast and online media. For more than a decade at the University of Saskatchewan, I worked to identify and shine a light on the innovative minds and discoveries at one of Canada’s top research universities.

We live in challenging times, where innovation and knowledge are often met with rejection and disbelief. This has consequences for issues critical to our species and our environment, from vaccines and genetic engineering to energy and climate change. I believe science writers and communicators have a vital role to play.