The Glasgow Climate Conference Part I: Good COP, bad COP

The Glasgow Climate Conference Part I: Good COP, bad COP

The 26th UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP26) was billed as our last best hope to avoid dangerous climate change. In Part I of this two-part blog, we see how the actual outcome surprised few but disappointed just about everyone.

Andrew Park

If last November’s COP26 meeting were a human being, it’d be an unreliable boyfriend. Unreliable boyfriends make big promises by the dozen. They’ll fix that hole in the back yard deck, they’ll pay their half of the rent on time, they’ll quit their addiction to unhealthy carbonated beverages. Years later, the deck’s unrepaired, the rent’s overdue, and the recycling bin is full of soda cans.

Unreliable boyfriends swear they’ll do better. “This time will be different,” he says, but in your heart, you know it won’t be. Similar behaviours were on display at COP26, the latest iteration of the United Nation’s annual “conferences of the parties,” whose goal is to reach international agreements on mitigating climate change . And while unreliable boyfriends make only one person miserable, the failure of successive COPs to produce climate-saving reductions in greenhouse gas emissions threatens future misery for humanity.

With so much at stake, then, where did COP26 go wrong, and were there any positive outcomes to the biggest COP ever?

Good COP

To grasp the positive outcomes of COP26, we have to understand that it was not one negotiation, but many. The official negotiations were aimed at recalculating each country’s nationally determined contribution (NDC) towards driving down carbon emissions and reaching consensus on future actions. Off to the side, however, negotiators engaged in a lot of horse trading over emissions targets for specific sectors. We saw sectoral agreements to end deforestation and land degradation by 2030, to reduce methane (CH4) emissions by 30 per cent below 2020 levels, and to accelerate transitions from coal to “clean power” and zero-emissions cars and vans.

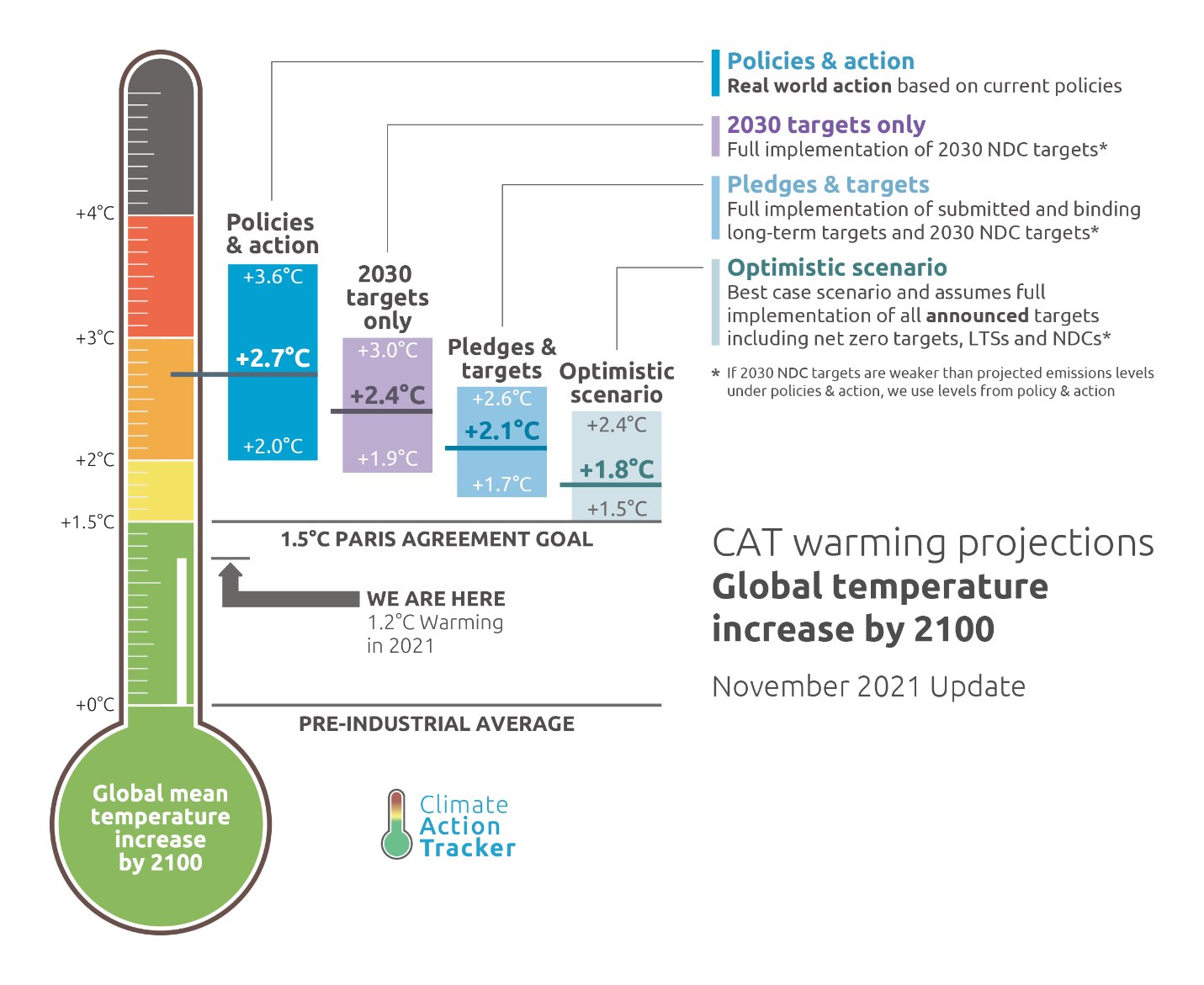

Updated NDCs and sectoral initiatives move the world incrementally closer to the Paris Agreement target of restraining global warming to less than 2oC degrees (and preferably only 1.5oC) above pre-industrial levels. According to Climate Action Tracker (CAT), full implementation of NDCs and pledges from Glasgow could reduce 21st Century warming an additional 0.6oC above what countries agreed to in Paris (see Figure 1). An optimistic scenario in which countries followed through on “net-zero” pledges might gain a further 0.2–0.7oC to actually put 1.5oC within reach—however remotely.

Net-zero targets lie far in the future for most countries, and our 2030 pledges leave an emissions gap of around 17–20 GtCO2e between the world and the 1.5oC target. A Gigatonne is one billion metric tons, and GtCO2e stands for gigatonnes of CO2 equivalents. The “equivalents” refers to the fact that greenhouse gasses with different heat trapping potentials have been converted into a common basis relative to CO2.

This wide emissions gap might be closed further if China and the USA were to follow through on their COP26 promise to share technology and push for greater ambition around the 1.5-degree goal. The two great powers account for over 40 per cent of global emissions, and if their agreement can survive geo-political wrangling over other issues, its future impacts on emissions will be considerable. Green member of parliament Elizabeth May, a veteran of many COP meetings, said in a later webinar post-COP 26 that she believes the agreement will stick because “China cannot afford to lose the third pole,” namely the Himalayan glaciers that are the source of Asia’s great rivers, including the Yellow and the Yangtse.

Figure 1. The Climate Action Tracker Thermometer reports the range of possibilities for mitigating global warming. Image courtesy of Climate Analytics and the New Climate Institute.

Bad COP

Although the good COP raised some cautious hopes for future climate action, the runup to COP26 was burdened with levels of pre-conference hype that were almost guaranteed to deliver disappointment. When your meeting is billed as “the last best hope to fight climate change,” there’s really no place to go but down.

Consider that climate negotiators from 190-plus countries were tasked with two conflicting goals. First, civil society, scientists, and even their political masters expected them to reach an agreement that kept the 1.5-degree target alive. But those same negotiators were also tasked with representing their countries’ narrow economic and political interests. The almost inevitable result was the tepid Glasgow Climate Pact, whose language was filled with lukewarm injunctions inviting, requesting, and urging countries to fulfill commitments, submit plans, or “consider” increased ambitions.

As with agreements achieved at Paris and other COPs, negotiators haggled over every word of the pact. In typical COP fashion, the final agreement was crafted at the last minute, multilateral huddles around breakout tables in the negotiations hall. All this word haggling eventually delivered language that most countries could live with.

“Live with” is a far cry from “happy about,” and a final disappointment arrived after the language of the pact had already been agreed. Before the pact could be formally adopted, US representative John Kerry got together with coal-dependent China, India, and South Africa in one last huddle to change a key phrase of the agreement. Indian environment minister Bhupender Yadav took the floor to announce that “…phase-out of unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies” would become “…phase-down of unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.”

Mexican climate envoy Camila Isabel Zepeda Lizama expressed what many felt when she said, “We believe we have been sidelined in a non-transparent and non-inclusive process. At the stocktake, we already compromised to what we perceived was an agreement by parties, even if we were unhappy with the text. But now we learn that there are even further changes that we were not been made aware.”

There were other disappointments at COP26. A number of countries, including Australia, The Russian Federation, Brazil, and Indonesia failed to increase their NDCs in line with the Paris Agreement. Others, including Canada, promised marginally increased NDCs. And the Paris Agreement promise that developed countries would deliver USD100 billion in mitigation and adaptation financing to the developing world remains unfulfilled.

At the end of the day, though, it’s those two little words, “phase-down” that will be the enduring legacy of “bad-COP26.”

This is part one in a blog series on COP26. Stay tuned for part two on April 13, 2022.